Shimmering Horizon

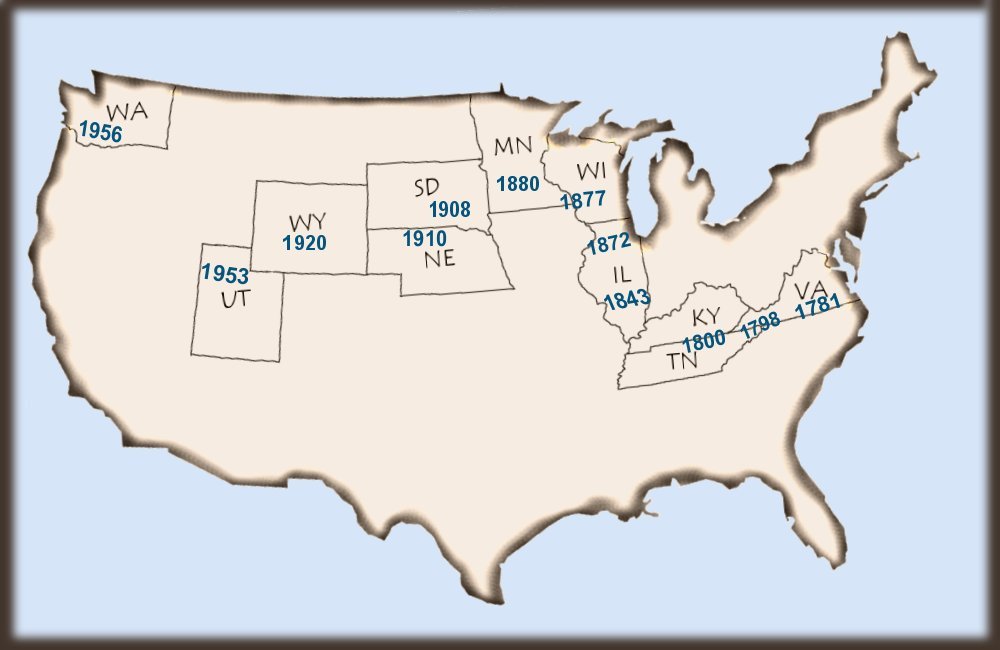

~ from Virginia and Tennessee to the Wild West ~

1781 through 1910

Dramatized family history

1781 : Chesapeake Bay

~ September 5 : Christ Church, Lancaster County, Virginia

When Rachel Chowning heard the clatter of hooves at a gallop, she set aside the basket of beans she'd been shelling and went to the cabin door.

"The British are coming!" boys' voices whooped from the lane.

"Ships sailing into the bay!"

"Warships! Cannons on deck!"

"Union Jack flying!"

"They've come to save General Cornwallis!"

The young riders thundered away, spreading the news.

Rachel's six-year-old son cheered after them from the top of the fence where he had clambered, barefoot in spite of the rough, prickly grass stubble in the yard.

"John," Rachel called. "Grab your jacket and boots."

"Why? It's plenty warm!"

"It's chilly on the point. Wind always blowing. Boots on. Get your jacket while I saddle the mare." She drew on her riding pantaloons beneath her skirts, tied on bonnet and shawl, and headed for the stable.

"Are we going to find Papa?" John climbed from a barrel to the top of the stall partition. "Will he be at the point?"

"No, he's far away." Rachel cinched saddle straps, turned the mare to the mounting block, then vaulted astride with a swirl of skirts. The army needed all the doctors they could get. Her husband, William Briscoe, had joined a year ago, an asset to the Republic even at the ripe old age of forty-one.

"Still treating sick soldiers?" John hopped across to the horse's rump.

"That's right. Now hold tight around my waist." The 25-year-old urged the mare to a trot. No need to ride lady-like, prim and proper, in times of war.

The lane led south out of the town of Christ Church. At the next settlement it swung southeast, and for twenty minutes they rode, spurring to an occasional canter.

Rachel slowed the mare to a cooling walk as they neared Windmill Point. They broke out of scrubby woodland, and Chesapeake Bay unfurled before them. The bay stretched inland to the left, clear up north to Baltimore and the mouth of the Susquehanna River.

A brisk sea wind blew from the north-northeast, welcome relief after the sweltering humidity of August. She could barely make out Cape Charles, twenty miles to the east, a smudge on the shimmering horizon.

Straight ahead to the southeast, the way to open ocean, a line of ships rode the swells. Prows first. Heading inland from the Atlantic. Sails billowing and flags flying. Flags bearing Britain's colors.

"I see them!" John cried in delight. "One, two, three--"

"We need a spyglass," Rachel said, squinting into the distance.

"Where are they going?"

"They'll try for Yorktown." Rachel waved to the right. "Two points down, at Yorktown. They must be trying to free General Cornwallis from the seige."

"Corn Wally? Who's that?"

Rachel curled her lip. "The British sent him to take control of our colony. Just two months ago he sailed in with his troops and started building a fort there. But the French are helping us. We have him surrounded. Now he can't get out, and he's stuck in there, short on food."

John looked out in the bay. "I see seventeen ships coming. What will they do?"

Rachel shaded her eyes against the midmorning glare. "I count nineteen. I think they'll try to chase away any American ships, and land more troops, and bring the general more provisions."

"Look, Mama, look! More ships! Where did they come from?"

It was Rachel's turn to whoop. "It's the French! They've been drawn up around Yorktown, keeping Cornwallis from coming out. Now they're going out to meet the enemy. Count them, John!"

The boy ticked off each ship as it heeled out into the bay, forming a rough line. "Twenty-four! We outnumber the British!"

"Stay in the saddle, high enough for a good view, while the mare grazes." Rachel Chowning dismounted. "I think we'll be here a while."

'Battle Off the Virginia Capes,' 19th century painting owned by the U.S. Navy and on display at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum in Norfolk, VA

~ September 5 : Greenbrier, Cape Henry, Virginia

Boom!

Rachel Laws startled. Tea sloshed from her cup.

The parson's wife gave a muffled yelp and clutched at her throat. "Oh my goodness, what was that? Oh my!" Another thunderclap followed hard on the first.

"I must be going now," the 23-year-old visitor said, setting down cup and saucer, and rising. "I'll just collect my children from the kitchen, and thank your cook for watching them."

"But what was it?"

"Cannon fire."

"Lord above! Who has cannons hereabouts?"

"I believe Cornwallis has one or two in his fort, although the direction seems off. Thank you kindly for your hospitality. I'll just let myself out." Rachel hurried down the hall.

Her four young children sat on the cool kitchen floor, cracking hazelnuts. Susannah, the five-year-old, pounded away like a blacksmith while Moses, age four, picked the nutmeats out. The two younger ones rolled nuts and giggled.

"Come," Rachel said. "Time to leave. Thank Cook for tending you."

"Thank you, Cook," Susannah said, handing over her hammer, echoed by Moses delivering the nutmeats bowl. The two little ones scampered out the door with hazelnuts clenched in fists.

Rachel lifted her brood one by one into the pony-cart, climbed to the seat, and flicked the reins, clucking at the pony. They set off on the ten-mile journey home. The lane wound around the north end of Cape Henry, giving a view northwest towards Yorktown, and directly north onto the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.

Early afternoon sun warmed her shoulders, but the wind nipped at her face as Rachel gawked at the sight. Two lines of warships formed a great V, drifting slowly east toward the Atlantic. The leaders fired at each other. Gunpowder flashed. Smoke plumed.

While she watched, the mainmast of one British ship toppled, the sails luffing like wings of a downed bird.

"What's happening, Mama?" Susannah asked.

"Our French friends are trying to drive off the new-come British."

"Which is which?"

"See the flags? The white and gold ones, those are French. British flags carry a red cross on top of a white one on a blue field."

"The new fort flies one of those."

"Yes, but for how long, I wonder? Look! There are more French ships than British."

Susannah cocked her head. "They're all sailing out to sea!"

The middle sections of the fighting lines had come in range of each other and joined in the fray, though the last ships merely followed in the wake, still too far apart.

"Boom, boom!" the younger children yelled, jumping around in the cart and laughing.

Rachel lingered, watching the combatants heeling hard in the wind, heading for open ocean.

She glanced toward Yorktown, perched within its fortifications on the cape to the northwest. American and French troops still surrounded the British fort. "Aaron, are you among them?" she whispered into the wind. "Please write. Let me know how you fare."

Her husband had vigor enough to last through most trials that came in a time of war, and a sharp mind to keep himself out of trouble. A natural leader, Aaron Davis might even have risen in the ranks by now.

"Boom, flash, boom!" Moses shouted.

"Wave goodbye to the brave ships now, children," Rachel said. "Sit down. We're on our way home."

It is author's conjecture that Rachel Chowning and Rachel Laws went out to witness the battle. They did, however, live just to north and south of Yorktown, on capes that jutted into Chesapeake Bay -- although the actual distances make it unlikely they could see much of the action.

"Chesapeake," meaning "mother of waters," was the name of the area as used by the Powhatan federation of tribes.

Later note: There's also a Greenbrier over the mountains in what is now West Virginia. It's not clear which site was the home of Rachel Laws Davis.

Details about the heat and prickly dry grass stubble: provided by my granddaughter Kate who lived in Virginia from age 3 to 7.

1798 : Virginia's coast to eastern Tennessee

John Briscoe's mother, Rachel Chowning, died when he was nine, and his father, when he was twenty. Now, at age 23 and alone in the world, John packed all his belongings and trekked inland to the town of Staunton where he hoped to join a company heading to the frontier.

Not only did he find a group led by Aaron Davis and his wife Rachel Laws, but he found, courted, and married an adventurous young woman from Maryland.

"Just look at all the muskets!" Nancy said to John as the travelers assembled. "What battle are they expecting? The British are long gone!"

"There are outlaws in the wilderness," he said. "And Sioux and Shawnee. There's no safety except in numbers. Well-armed numbers."

"Where's your musket?"

John drew a tarnished saber from a scabbard lashed to his pack. "My grandfather's legacy will have to do. I didn't have enough money for both an ox and a musket. Not nearly as deadly as a firearm, but better far than a fiddlestick's end."

"A what?"

He snatched a stick from the ground and brandished it. "Surrender or I shall tickle your ribs!"

She laughed. "A better use for a fiddlestick in war would be for me to play the violin in the front lines. How could the foe fight on with hands clapped over ears?" She glanced over the armed men again and bit her lip in contemplation. "Fiddlesticks."

"Are you regretting this?" John asked, sheathing the saber. "We're leaving civilization, heading for a rugged life in a rugged land. It won't be easy."

Nancy Steele shook her head and squared her shoulders, living up to her family name. "I'm eager to try my hand on the frontier. Just stow our pitchfork where I can reach it in a pinch."

* * *

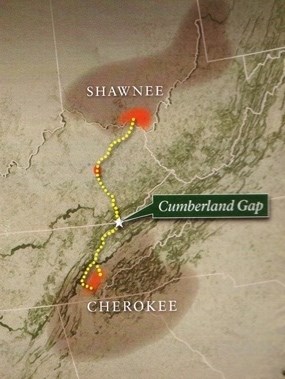

The Davis party took to the Great Road. The rough-hewn track ran southwest along the foothills of the rumpled Appalachian Mountains, a forbidding wall between coastal hinterlands and the vast mysterious continent beyond.

On the tenth evening, as the travelers neared Christiansburg, the sky darkened early. Surly clouds towered above the mountains in the west. Breezes blew in fits, heavy and humid, and the forest's dry autumn canopy hummed and shivered.

Rachel Laws Davis guided the first oxcart in the line while her husband and son-in-law scouted ahead. She eyed the threatening storm. So did the oxen, snuffling as if smelling danger. She glanced around. "Aaron-lad!" she called to her thirteen-year-old son who kept the hog in line with a willow switch. "Where's Thomas?"

"Still with Susannah."

"I don't see her cart."

"They slowed near the last glade so Thomas could chase fireflies."

"Run back and fetch him. I'll keep an eye on the hog."

Stormclouds roiled overhead by the time Young Aaron came loping back with his little brother in tow.

"Mama, see what I caught!" the five-year-old cried, holding up clenched hands. "It flashes like--"

Lightning blazed. Thunder boomed, echoes rumbling down the mountain flanks. The oxen shied, swerving the oxcart. The hog squealed and plunged into the undergrowth.

Startled, Thomas loosened his grip, and the lightning bug spiraled away, blinking, a tiny reflection of the next blaze overhead.

Young Aaron shouted and ran after the hog.

Thunder rolled again.

Hooves sounded from ahead on the trail. Aaron Sr arrived in time to help wrangle the panicking oxen. A blast of wind swept down from the heights, snatching his hat and whirling it into the gloom in the midst of a flurry of sycamore leaves.

"Almost there," he shouted against the howl of the storm. "Only a mile to go."

"It's going to be a long wet mile," Rachel answered, and sure enough, the boiling clouds burst in a torrent of icy rain.

* * *

The morning after the storm, the travelers emerged from shelter and formed up again, inspecting their carts and livestock while airing their drenched belongings.

"I've never seen such lightning," Rachel told the innkeeper.

He chuckled. "That's life in the mountains. The thunder comes rolling down like a stampede from the heights."

Little Thomas piped up. "I was catching lightning bugs by the road, and they got mad and made big lightning!"

"Spooked our oxen, nearly overturned our cart, all because of a handful of fireflies," Rachel said, smiling and mussing Thomas' hair.

The mountains breeze ruffled her husband's hair as well. Aaron Sr kept hand to brow to shade his eyes from the morning sunlight.

"Your pa don't have a hat," someone commented to Aaron Jr.

The thirteen-year-old turned from the ox he'd been brushing to see a boy near his own age. "The storm stole it last night. I ran back and hunted, come daybreak, but no sign of it."

"He'll need a hat, wherever you're going." The boy chewed a wisp of straw and rocked on his heels, gazing up and down the line of travelers.

"We're off for Tennessee," Aaron said. "Going to homestead in the wilds."

"Not so wild anymore. My pa has an inn in Morristown. Lots of folks homesteading all along the Wilderness Road."

"You been there?"

"Born there."

"Your pa's still there?"

"Yup. All my family, too.'

"But you're here."

"Yup. Seeking my fortune."

"Really?" Aaron mulled that over. Could he go seek his fortune, too? Strike off, all on his own?

"He'll need a hat," the other boy repeated. "I know where to find a hatter."

"We don't have much money."

"The hatter'll take trade. And your pa will really truly need a hat if he's going to Tennessee."

Aaron looked at the family oxcart. What could they spare to give in trade? His big sister Susannah had walked up the line to talk to their parents. She had her own oxcart, and a husband and baby as well.

Aaron's old yellow dog wound a way between oxen legs, her half-grown puppies trailing along. "Would a young hound be enough for a hat?" he asked.

The other boy squatted and whistled, and two puppies galloped to greet him. "Would you make a bear dog?" he asked the male, and tussled in play. "You're a strong one. Look at those big paws."

"I'll tell my pa what you say," Aaron said. "Where's the hatter? Can you point us the way to his shop?"

"I'll take you there myself." The boy grinned. "I'm his apprentice. Want to make sure he knows it's me who brought in the trade!"

Aaron laughed and punched the boy's shoulder.

He got a return blow that knocked him to the ground. Boys and dogs wrestled and tumbled until Aaron Sr waded into the good-natured fight and split them up. "You're spooking the oxen."

"Sorry, Pa," young Aaron said as he got to his feet. "But good news! I know where to get you a new hat, thanks to -- um--"

"Davy," the boy said, holding out a hand. "Davy Crockett from Tennessee. Apprentice to Christiansburg's only hatter. Follow me, sir, and we'll see if Mr Snider will take a bear-dog pup in trade."

* * *

Aaron Davis, in a new felt hat, led the company out for the next leg of their journey to Tennessee. Longhunters like Daniel Boone had been spreading word for a decade or so about further lengths of the trail that led around the southern reach of the Appalachians to unclaimed hills and wide open prairie lands. North Carolina now was offering land grants in the Powell River Valley.

The track wound through heavy forestland, climbing the rough terrain of Virginia's southwestern reaches. The Davis party fended off one Shawnee raiding party and twice skirmished with vagabonds lying in wait. Nancy Steele brandished her pitchfork, and John Briscoe, his sword, but volleys of musket-fire sufficed to drive off the attackers.

The rough map Aaron carried gave little clue to their progress. Landmarks didn't look much like their descriptions. Rachel was glad they had a trail-toughened guide who had safely led many parties of settlers through the wilderness. Their path wound south into the new state of Tennessee, then veered to the northwest, still climbing.

Susannah huffed and panted as she trudged up another slope. "I see a peak straight ahead," she told Nancy. A quick friendship had sprung up between the two young wives.

"Fiddlesticks!" Nancy moaned in dismay, staring through the break in the trees at the skyline, looming like a great wave about to crash. "They said there was a way around the mountains. Surely we can't get the oxcarts over that range!"

"The Cumberland Gap," the guide announced from further up the trail.

Nancy and Susannah rounded the next turn, took one look, and heaved sighs of relief. A great gash in the mountains showed blue sky ahead. One last ascent would take them to the pass.

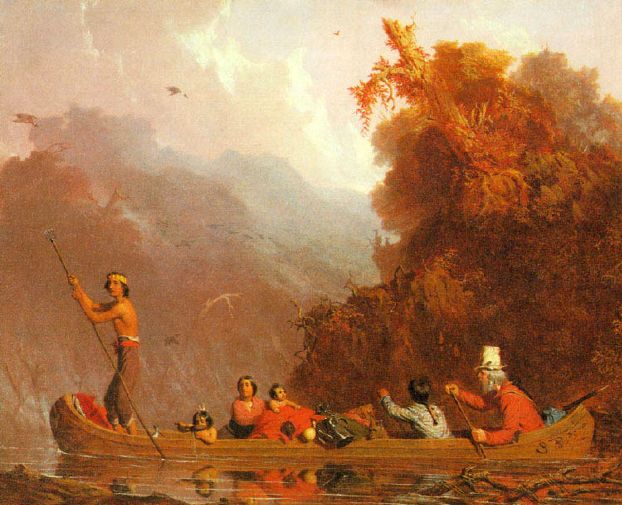

'Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap,' 1851 or 1852, by George Caleb Bingham

Not long after crossing through the Gap, the guide pulled the company to a stop. "Your land claims lie ten, fifteen miles thataway," he told Aaron Davis, pointing west-southwest. "Follow this creek till it peters out and keep going, straight on. I'll take my last payment now and bid you farewell."

"We hired you to take us all the way!"

"If you can't lead yourself for ten miles, you shouldn't ought to be out here, homesteading." The guide held out his hand.

Aaron looked around the group, sighed, then paid the man.

That last ten-mile stretch took nearly a week to travel, for they had to cut their own road. Hickory and poplar, sycamore and oak stood like an army in their path. At last they reached a stretch of unnamed creek that matched the description of their land claim.

After the end of their long travels came not rest but more hard labor. Each homesteader's stake of 400-some acres needed a rough cabin raised, and fields cleared and plowed. Then the men went hunting for elk, deer, and bear while the women and children planted potatoes, and tended the hogs and chickens. Too late in the season to sow corn, and not enough fields yet for wheat.

The homesteaders stayed knit in fellowship after their long trek, helping each other with plowing and barn-raising through the following years. Aaron and Rachel Davis seemed always at the heart of the scattered settlement, and before long this newly cultivated watershed took the name of Davis Creek.

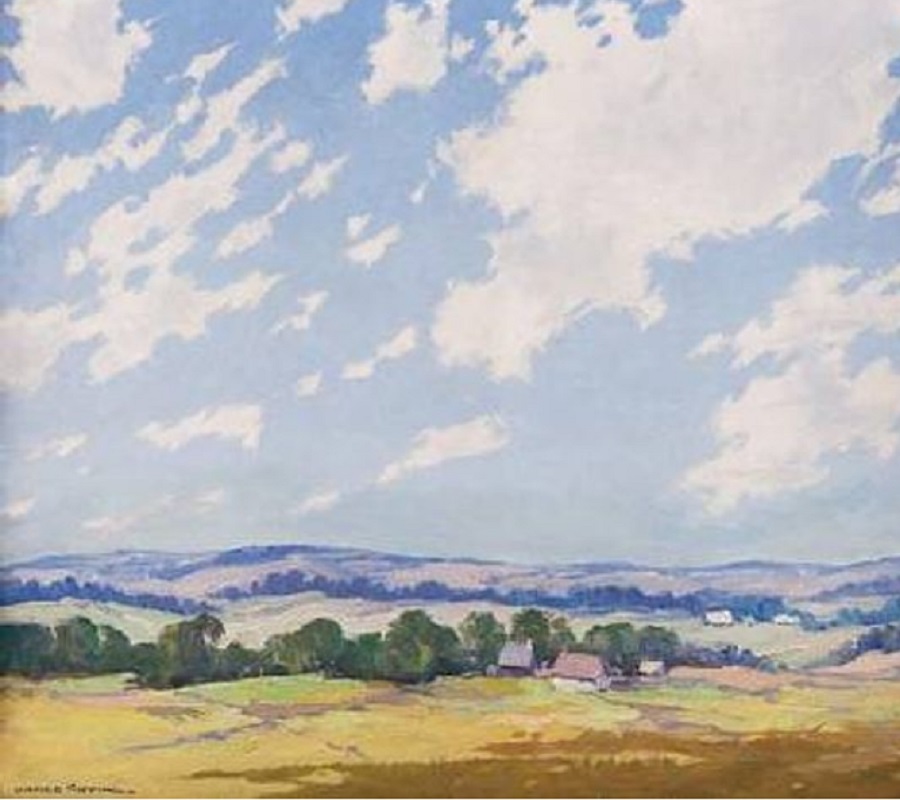

view over Claiborne County, Tennessee -- Davis Creek's corner of the state

Story premise: The two families met while forming a company for safe travel. I'm giving the Davises two yoke of oxen and an oxcart, a large spotted hog, a tall Shanghai rooster, an old yeller dog. (Song: Sweet Betsy from Pike)

Details about Virginia's fireflies and summer thunderstorms provided by my daughter Sharon who lived near Christiansburg, Virgina, for several years.

1800 : Davis Creek, Tennessee

In 1800, Rachel Laws Davis tended her daughter Susannah through the birth of a second child, a little boy. And then she tended Susannah's friend Nancy Briscoe through the birth of her first baby.

After the ordeal, Rachel ducked out through the cabin's low doorway. "It's a beautiful little girl," she told Nancy's husband. John had been pacing outdoors for hours. "Congratulations! Do you have a name for her?"

He grinned. "We do indeed. Nancy agreed we should name her after my mother."

"And her name is--?" Rachel Laws prompted.

"Was. Her name was Rachel Chowning."

Reminder: Most incidental details, like this scene, are products of the author's imagination, built on a frame of names, dates, and events like births.

1809 : Davis Creek, Tennessee

Nine-year-old Rachel Briscoe spent a long day

tending Susannah's sixth child, Silas,

a tireless little two-year-old. They fed chickens,

gathered eggs, swept the Briscoe cabin,

hoed in the corn patch, picked wildflowers,

and played with a litter of puppies in the barn.

"Go home now?" Silas asked for the hundredth time.

Rachel gave the same answer. "When your big brother comes for you. After the baby is born."

"Baby like this?" He held up one of the puppies.

She laughed. "Your baby will be pink like a piglet. No floppy ears. No tail."

"Woof!" Silas said.

"I wonder what they'll name your baby."

"Woof!"

"No, I don't think so. Hey, what shall we call this puppy? Help me find a good name."

"Pompom! Call him Pompom."

Rachel laughed and patted the pup's fluffy head. "Why not? Pompom it is!"

The name for this fictional puppy provided by my little grandson Oliver.

1813: Davis Creek, Tennessee

Old Henry returned from a long-delayed trek to Knoxville, some sixty miles away, bringing a packet of mail for the Davis Creek settlers. He also brought stale news. "We've been at war for a year! The Brits ha' been attacking towns on New York's coast, and running like pirates on the St Lawrence River."

"They don't really expect to subjugate us again, do they?" Nancy asked John.

He shook his head. "There's no going back. We've been an independent nation for 37 years now."

"That's how old you are, Ma!" Silas whispered to Susannah.

"Yes. I'm the same age as our country. Born the year of the Declaration."

Her husband, James Griffitts, pushed to the front of the crowd. "Are they still rallying troops?"

Susannah shot James a worried glance. He had planned on joining the Tennessee militia to do his part in the brewing conflict which would come to be called the War of 1812. She shuddered. Her father, Aaron Davis, still talked about the horrors he'd seen in the battle for independence.

Old Henry snorted. "Nope. Too late. You missed the boat."

Susannah heaved a long sigh of relief. James wouldn't be leaving the safety of these secluded mountains.

"Let the Yanks handle that, anyway, way up north. What's it to us?" Old Henry hawked and spat in the dust. "Now you'll never guess what I saw rolling down the middle of Knoxville. Wagon-loads of Africans, all trussed up in chains, getting packed off to the west side of the state. I hear tell they got more cotton plantations than ever, popping up all over, down on the flatlands."

An uncomfortable silence fell among the listeners. They'd come to Tennessee under the impression it would be a free state, but the plantation lobby had overturned those plans.

"Thought I'd buy a string to help us out here in Davis Creek," Old Henry drawled, then guffawed. "A joke, folks, a joke!"

"Besides the fact none of us could afford a slave," John Briscoe growled, "you know our feelings on the subject."

Old Henry tipped his hat in apology, then rattled on. "The war, they say, has put the damper on plans for the new territory. You know, the Louisiana Purchase, t'other side of the Mississippi. Some folks want it opened right up for settlement. The sooner the better." He scratched his beard. "Let's see. Somethin' else I was gonna tell about. Oh yeah. They asked if we'd seen anythin' of that chief from Ohio, Tecumseh. He's been quartering the land from Iowa to Florida, trying to get all the tribes to unite in a nation of their own and stop the push of civilization into the west. He's sayin' it's their native land, not the Yanks'."

"Why would Tecumseh come here?" Rachel Briscoe asked her father.

John rested a hand on her shoulder. "Good question. The Cherokee didn't actually live in these parts. Before they sold this wilderness off in land deals, they used these mountains for hunting grounds, or for battle grounds when they bickered with the Shawnee."

the Warriors' Path

"Anyway," Old Henry said, "last they heard he was stirring up the Creek tribe down Alabama way. Tecumseh's confederation is siding with the Brits in the war, stirring up trouble wherever they can."

Aaron and Rachel Davis joined the group. "What's all the hullabaloo?"

With relish, Old Henry launched into the tale again. Nothing perks up life in the backwoods like a heap of tidings from the wider world.

Rachel Briscoe felt torn, thinking of Tecumseh's slogan. It's our native land. If you looked at it collectively, the native land of her folk was Virginia. Before that, England.

But she herself, a person all independent, thirteen years old and almost grown -- she had been born here in Tennessee. Didn't that make this state her own native land as well? If she had the power to choose, if she was to be great-hearted and give this valley back to the Cherokees, where would she call home?

Cast out, adrift, torn from her roots. The prospect, though only an imagined fancy, made her feel homesick.

Rachel's thoughts turned from red skin to black. How homesick the African slaves must feel, torn so far from their own homeland, stripped of dignity, bound to heavy labor, trammeled into the dust.

Story premise: The Davis Creek community figured war was likely with the Brits, and knew of widespread clashes with the natives, but being tucked so far up in the back country, didn't hear the call to arms until long after the muster.

Old Henry is a fictitious character, but Tecumseh steps right out of history. (Real life background for Orson Scott Card's novel Red Prophet!)

1814-1815: Davis Creek, Tennessee

Susannah's husband James made several trips to Knoxville the next summer, and so heard the news when it was still fresh. Britain had finally defeated Napoleon, and now was feeding all its strength into campaigns against the young, upstart United States. Word came that they planned to capture New Orleans and clamp down on American traffic on the Mississippi River.

James enlisted in the Tennessee militia, galloped home to settle his family for the season, then gathered up rifle and camp gear and rode out again to serve under Andrew Jackson.

Silas and his older brothers shouldered the heavy work of the family farm, and the girls helped their mother manage the rest, laboring dawn to dusk. "We'll keep too busy to worry," Susannah told them. But she fretted just the same.

* * *

James returned home the following spring, haggard but jaunty. "We didn't even have five thousand men against their eight thousand," he boasted, "but we kept 'em four miles out of New Orleans. They tried to outflank us, capture our own battery and turn it on us, but couldn't slog through the marshes. Then their main force came charging up to our earthworks, but they forgot to bring the assault ladders! They were stuck in the mud right there in easy range. It was a massacre."

Susannah clung to him. "Thank God you came back safe!"

James swung her around and kissed her. "We all came back safe, all but thirteen. Thirteen! Who ever heard of such light casualties! Now who's this fine fellow trying to hide behind your skirts?"

"Your youngest."

Silas swooped up his little brother. "This is Pa," he told the child. "He went a-soldiering and won the war. Give him a big hurrah!"

1817-1819 : eastern Tennessee to western Illinois

Seventeen-year-old Rachel Briscoe ran along the path

from her family's homestead to the Griffitts farm,

a bag bumping at her side and a bundle squirming in her arms.

"Silas!" she yelled when she saw the ten-year-old taking the hogs out to forage. "A company just passed through the Gap on their way to Illinois, and we're joining them. Not going to wait till tomorrow after all. Will you give this to your mother? My mother says to tell her 'Farewell,' and to make good use of the linen." Rachel swung the bag from her shoulder.

"Sure," he said, and slung it onto his own back. He cocked his head at her other parcel. "What's that? A chicken for our dinner?"

A nose poked out, snuffling.

"Hardly. I remembered you asking for one of the litter, and they've finally weaned. Just in time."

The boy yipped in joy and took the wriggling puppy, which yipped in answer. "What's its name?" Silas asked.

"Isaac's been calling it Jesse. We never know whether he's calling the dog or yelling for your brother! You can change the name, if you want." Rachel glanced around the farmyard, but no sign of Silas' big brother William, her own age. She sighed in wistful regret. "Tell your family goodbye for us. I hope we'll meet again someday!"

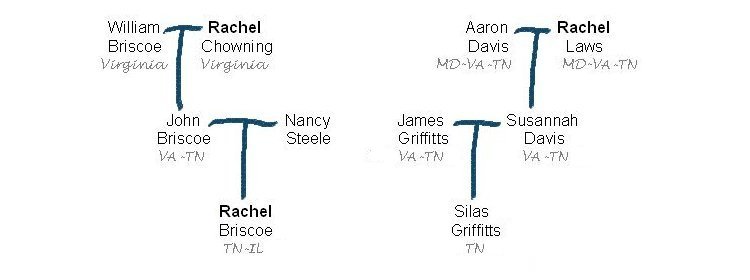

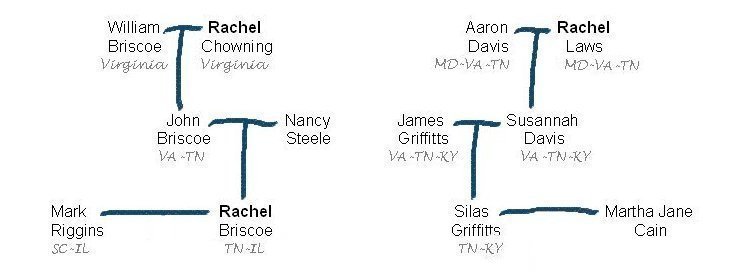

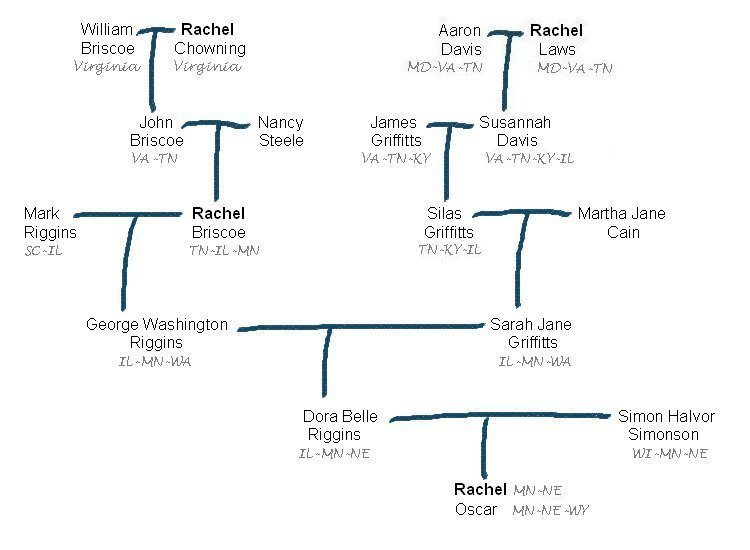

chart of the families in 1817

Rachel set out with her family on the Wilderness Road, heading northwest into Kentucky. As they journeyed, John and Nancy spun their children tales of their own trek from Virginia, how they had to walk the whole way, not even a cart or musket to their name. Now the youngsters took turns riding in a covered wagon loaded with blankets, canvas, pots and pans, and barrels of seed and provisions. Plus a pitchfork and an old saber.

The well-traveled track led down from the mountains onto a vast plateau, forested by poplar, oak, and chestnut. For a stretch the road made use of an old bison trace, a well-trampled pathway leading to a salt lick.

Whenever John spotted a wild turkey, he'd prime the musket Old Henry had traded to him and secure fresh meat for their evening meal, glad he didn't have to chase down the fowls with nothing but a long blade.

The Briscoes traveled west across the state of Kentucky. The horizon stretched out flat as a plate. No knolls, no hills, and certainly no mountains.

On they traveled, into Illinois territory, all the way to the lowlands of the fabled Mississippi River. Rachel delighted in spotting great blue herons and brilliant white egrets in the marshes.

John and Nancy bought property in Brown County, and the whole family set to work on a cabin.

'Clouds Over Illinois,' by James Topping (1879 - 1948)

Before the Briscoes finished raising a barn, Illinois entered the union as the 21st state.

At the county celebration, Rachel and her little sister ambled about the stalls while their brothers dashed off to a tug-o-war. They watched a boxing match and a barrel-walking race and ended up at a pie-eating contest. Several big beefy farmhands lined up at the table, tucking cloth napkins into collars. A plump country wife joined them, to a few titters. She grinned right back.

A wiry red-haired fellow announced the names of the contestants, spinning jokes about former wins and notorious appetites, counting down and launching the competition, rousing the crowd to cheer for their favorites.

Rachel's sister bounced on tip-toes, giggling at the messy sight. "Is there a contest for kids? I want to try!"

"We'll ask in a minute. Won't be long now."

In moments the announcer declared a winner, hoisting the man's arm and raising more laughs about the fellow's new hair style, sticky with berry filling.

When the crowd broke up, Rachel let herself be dragged to the stand. "Sorry," the announcer answered. No contest planned for children. But he had a pie left over, if they cared to share it with him.

Mark Riggins fed them jokes as well as pie, and gabbed with Rachel the rest of the afternoon. "The blarney tongue," he admitted. "Comes with the hair and the luck of the Irish. The family name used to be Regan, back in the day. From Ireland, by way of South Carolina."

Rachel liked Mark's dash and charm and wit. She made for a rapt audience, which always pleases a talker, and after the fair wound down and everyone went home, he came a-courting.

The next year saw the merriest wedding. Neither bride nor groom could keep a straight face through the ceremony.

A very flustered pastor left afterward, shaking his head and clutching his Bible for comfort.

The name for the fictional puppy: provided by my grandson Thomas ... whose first name is Isaac, like Rachel's brother!

There's no record of Mark's hair color, but red appeared in later generations, and he was one-eighth Irish in ancestry. Two of his great-great-grandparents, Daniell Ryan Regan and wife Elizabeth, had immigrated from Ireland in the mid-1600s.

1824 : Davis Creek, Tennessee

Rachel Laws Davis brought her daughter Susannah two well-packed lunch baskets. It took a lot to feed a family of eleven. "I'll miss you," she told her eldest. "But I understand your quest. Your father and I did the same."

"You were much younger when you embarked on your grand adventure!" Susannah stretched her aching middle-aged back, then hugged her mother goodbye. "Well, I suppose we'll manage. My young-uns are big enough to pick me up if I stumble. Even my little Silas."

The seventeen-year-old topped both his mother and grandmother. He leaned down for a hug. "Thank you for the packet of paper, Gramma Rachel. And all the penmanship lessons."

"Don't want you to grow up with such a crabbed hand as your grampa."

"Hey!" Aaron protested with a mock scowl.

"So you'd better use some of that paper to keep in touch."

"I'll write whenever there's news."

"And I'll always write back."

Rachel and Aaron, in their 60s, waved goodbye to Susannah and James, in their 40s. The Griffitts family, including several strapping sons, set out with two covered wagons, four yoke of oxen, and assorted other livestock. They followed the same frontier road as the Briscoes had taken, but made a shorter journey of it. They bought land in Laurel County, Kentucky, and set down roots.

Rachel eagerly opened Silas' first letter, telling about the sights along his family's trek. He'd hoped to see a buffalo, but folks said there weren't any more in those parts. Might still be some west of the Mississippi.

He told about the new homestead and gave the name of the post office where they'd get their mail. She read the letter aloud to Aaron, whose eyes could no longer handle close work, and included his greeting when she wrote back.

Silas wrote again, about the progress of the family farm, and the odd jobs he'd taken to help tide them over.

Rachel had to smile at the youth's description of the young women he encountered at barn dances and county festivals. She answered every letter, and twisted Aaron's arm at least to sign his name.

"Chicken scratches," he chortled. "Not worth a heap of beans."

"Grampa's chicken scratches are worth more than silver or gold."

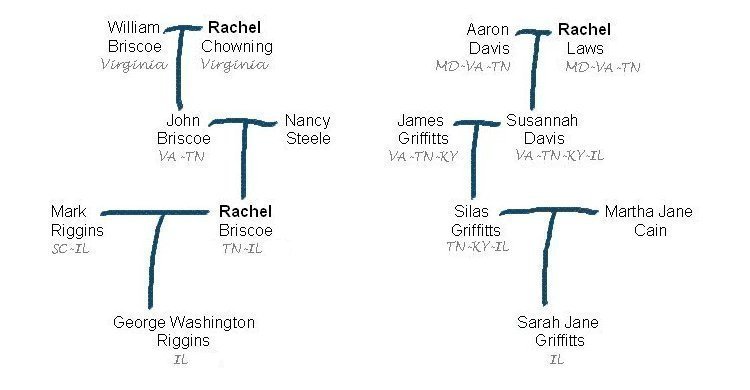

chart of the families in 1824

In 1826, after a long dry spell as far as letters went, Silas wrote he was about to get married to a young woman by the name of Martha Jane.

Ten months later, he wrote of the birth of his first child, and in 1827, of his second. "I sing them the milking song you taught me, Gramma!"

No date is given for the Griffitts' move to Kentucky. It occurred sometime after 1812 and before 1826, according to the birth dates and places of their children and grandchildren.

1829-1834 : Davis Creek, Tennessee

Early in 1829, Rachel read another letter aloud to Aaron. Silas, now 22, wrote that he was moving his little family to Illinois. His parents Susannah and James (now in their 50s) would be staying in Laurel County, Kentucky, along with his older brothers and their families.

She wrote a reply, and ended with Aaron's message. "Your Grampa says, 'Push that frontier beyond the horizon, young man!'"

Several months later came another letter, giving postal information about Morgan County, Illinois, and news that Martha Jane was expecting again.

In the autumn, Silas wrote of an unexpected reunion. "I took my wife and children to the big harvest festival in Brown County, and who should I run into but Rachel Briscoe! She's married now, to a short red-haired fellow who glowered like an angry bull. I think the fellow thought I was an old flame!

"Then Martha Jane joined us, her so plump now and all. Got that misunderstanding settled. They have five children, including a babe, and live in Brown County, just a hop, skip, and a jump to the west of us. Rachel was showing a prize hog at the fair. Brought back to mind my chore of chasing hogs through the woods at Davis Creek.

"I'm sorry to tell that Rachel's father John Briscoe died four years ago. Her mother Nancy moved in with Rachel and Mark. Nancy did not come to the fair that day, so I sent greetings with Rachel."

Gramma Rachel wrote back, "We too have moved in with family. Your Uncle Harmon gave us a corner. At seventy-one, we couldn't keep our own place running. We don't eat much. I can help with the laundry, and your Grampa is still chasing hogs. When he's not laid up with the rheumatics, that is. Like always, he sends his greetings. Says his chicken scratch is worse than ever, and not even a chicken could read it. I say he needs glasses."

* * *

In 1832, Rachel ripped open an envelope, assuming it came from her grandson Silas, but it was her daughter Susannah, still in Laurel County, Kentucky, telling of the death of her husband, James. He was only 54.

Rachel put down the letter and pressed trembling fingers to forehead. Tears dripped on Susannah's letter. "Oh dear God, spare me such a fate. I don't think I could bear losing Aaron!"

* * *

In 1833, wearing his new-fangled glasses, Aaron Davis sat down with pen and paper, and scribed in chicken-scratch to his grandson. "Dear Silas, it is with a broken heart I must tell you of your Gramma's passing. She was seventy-five years old. She treasured every letter you sent her, keeping them all in a bundle tied with a ribbon. Thank you for bringing her such joy each time you wrote."

The following year, Uncle Harmon wrote Silas to let him know that Grampa Aaron Davis, the pillar of Davis Creek, had gone to join Gramma in her heavenly reward.

1843: Brown County, Illinois

At the county fairgrounds, Rachel Briscoe was brushing down her finest hog when someone leaned on the fencing, making the rail groan. She looked up, saw Silas Griffitts, and grinned. "Ah-hah! I see you know where to find me. Think I'll win a prize this year?"

"If not, I'll buy you lunch after the contest."

"Me and all my kids?"

"How many do you have now?"

"Nine."

Silas whistled. "That's a few! One more than I have, myself."

"Enough for a good old game of tug-o-war. Here's my seven-year-old, George, bringing a pail of slop for Daisy."

"My name's George Washington Riggins," the boy proclaimed, thumping down the bucket and tossing back a mop of auburn hair. "I'm namesake of the first president."

"Why, I believe you're right. That was his name," Silas said. He looked around. "There's one of mine. Sarah Jane! Come see my old friend and her hog!"

A girl in pinafore and bonnet wove through the crowd and stood beside Silas. "You don't look old, ma'am," she said.

Rachel laughed. "Forty-three is old enough."

"I meant," Silas said, putting a hand on Sarah Jane's shoulder, "a friend from good old times when we were children back in Tennessee. I used to chase ugly hogs through the woods. Not lovely ones like this champion here. All she needs is a ribbon on her curly tail."

George and Sarah Jane sat on the fence rails while the two grown-ups told about living on the wild frontier, up in the trackless, forested mountains.

"Yup, that was rugged country," Silas said. "Prairie land still feels odd to my bones. No real hills in sight. Skyline flat as an anvil. We've moved to flat-as-flat Hancock County, by the way. Are you still in Brown?"

Rachel nodded.

"You enter a hog every year?"

"Most years."

"I'll always make the hog pens my first stop at the fair, then." He glanced at the sun. "Well, Sarah Jane, we'd better go find your ma and help her with the little ones."

Sarah Jane hopped down from the fence. "Goodbye, George," she said, and curtsied the way grown-ups did at the festival dances.

George bowed from his perch and almost fell into the hog pen.

"Don't forget your promise to buy us lunch!" Rachel called.

"Only if your Daisy doesn't win. I think my pocketbook is safe."

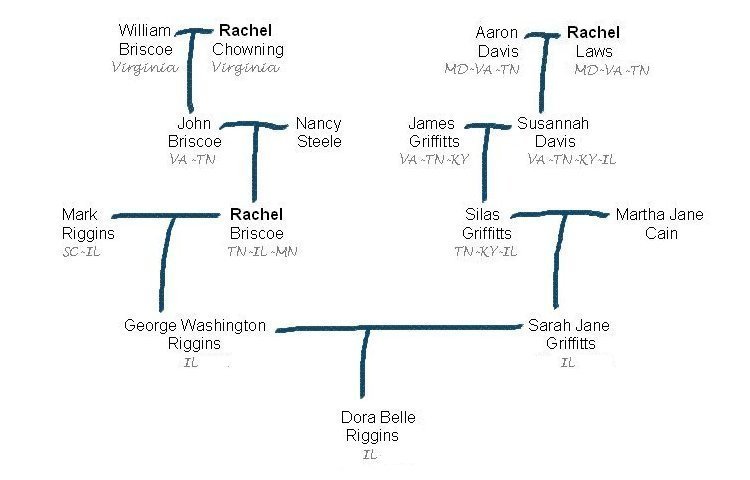

chart of the families in 1843

The name for this fictional hog: provided by my grandson John.

1844-1845: Hancock County, Illinois

One warm day the next May, Silas' eldest son strode in the door and took a proud stance, waiting for a reaction from his parents.

Silas gave a glance, then did a double-take. Thomas wore the jacket and cap of the Carthage Greys. "You joined the militia!"

"Captain Smith said I'm close enough to eighteen to count."

Martha touched fingers to lips, then found a smile. "My, you look fine in uniform! But you could have waited three months more, couldn't you?"

"Hah! I'm tall and strong as any new recruit. And I aim to be ready to serve if the need should arise." Thomas clicked his heels and did a slick about-face.

"Do you have to provide your own rifle?" Silas asked. The bore on his own had gotten bent in a broken-axle disaster with the wagon.

"Nope. That new tax pays for militia weapons. The shipment's s'posed to arrive before our first parade. We drill on Saturdays down by the courthouse." He strutted to the washroom to ogle his reflection in the shaving mirror.

"If the need should arise," Martha echoed. "I devoutly hope we've seen the end of wars."

* * *

A month later, the governor of Illinois ordered the Carthage Greys to guard the town jail. "Rumors of a mob intending to swarm the place," Thomas told his parents after getting off duty. "Planning to lynch the prisoners."

"Those fellows from Nauvoo?" Silas asked, and Thomas nodded. Silas shook his head in disgust. "What's it coming to these days? A mob. Tempers flaring out of all bounds. Can't sit back and wait for the due process of justice to carry out."

"Heaven help us if mob rule takes over," Martha said. "One lynching always leads to another, and then no one is safe."

A couple weeks later, as Thomas was walking home after guard duty, he heard an uproar behind him. He turned and ran back to the jail.

A crowd milled around the open door. Must have been a hundred men. Thomas heard shouts and yells -- and then gunshots. From inside.

More shouts. More yells. Then the mob broke up. Men dashed off in all directions. Silence fell -- a grim, dire silence.

Thomas moved ahead. He found fellow militiamen rising from the ground, searching for firearms thrown about, dusting themselves off. "Where's Captain Smith?" he asked, and they nodded toward the doorway.

Thomas stood, shifting from foot to foot. The other militiamen had been awfully close-lipped lately. He was a new recruit. He had no say. But shouldn't someone be doing something? "I'll keep watch," he offered. "Warn the mob off if they come back."

Someone muttered assent.

So Thomas stalked the outer perimeter of the grounds, and did not see the two bodies lying where they had leaped from a window, but leaped too late.

* * *

Next year, Silas Griffitts and his younger brother Jesse served as jurors in the trial of the alleged murderers of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Nine men had been indicted. Four fled for parts unknown, including the trigger-men.

The five remaining were acquitted in the end.

1847 : Brown and Hancock Counties, Illinois

Each year at the harvest festival, Silas Griffitts gave Rachel Briscoe a new tally. By 1847 his brood numbered twelve -- and of them, four children under age four. "Martha has her hands full," he told Rachel. "Thank goodness for Sarah Jane. She can diaper two babies quicker than I can do one."

The same day he got that first delightful smile from the newest baby, his oldest son, Thomas, went off to fight in the Spanish American War.

1854 : Brown County, Illinois

Rachel Briscoe Riggins did not go to the harvest festival in 1850, the year her mother Nancy died, nor in 1853, when her husband died. Mark Riggins had just turned 60 before his death.

Rachel now found herself the matriarch of her family. "I'm only fifty-four," she muttered to herself as she dressed for the fair. "Too young to be a matriarch. Ooh, fiddlesticks! My back does not agree."

She limped out to the barn and surveyed the hogs. The best of the batch had just rolled in mud. The oxcart for transporting the hog had a squeaky axle. Clean up the hog and endure the squeal all the way to the festival? Let the hog walk behind a saddle-horse?

Fifty-four suddenly felt ancient. "Go back to your wallow," she told the hog, and called young John to harness the pony-cart instead.

In the house she gathered up her lunch basket, shawl, and parasol. "George, are you coming to the festival?"

He strutted from the washroom. "Yes indeed." His hair was slicked, his shirt brushed, his suspenders sitting snug on his shoulders for once. He had topped off with his father's best felt hat, well-brushed, and offered an elbow to his mother. "Off we go!"

Rachel caught a whiff of cologne and smiled to herself. She knew what an eighteen-year-old looked for at the fair.

* * *

Rachel Briscoe waited by the hog pens until she spotted Silas Griffitts. "Not this year," she said in answer to his questioning look. "I aim to simply enjoy myself."

His wife Martha joined them to amble about the festival and take in the sights. The youngest Griffitts child was seven, and Rachel's youngest was John, at fourteen -- old enough to fend for themselves at the community event. They were sure to turn up, come mealtime.

* * *

When George Riggins found Sarah Jane Griffitts, the two of them strolled the grounds as they had done every year for the last three. Come mealtime, they had more important things to do than join family, although family was precisely the thing they discussed.

They found their parents in time for a serving of apple pie. Dessert first, announcement second. George had just secured a job in Hancock County, and a cabin not far from the Griffitts' farm. "So Sarah Jane can easily come home for visits," he explained. "You see, we mean to marry."

The younger brothers and sisters whooped. The girls showered seventeen-year-old Sarah Jane with hugs and kisses, while John stole George's hat and ruffled his hair. "You'll have a whole passel of red-headed babies!" he teased.

* * *

A few weeks later, the great-grandson of Rachel Chowning married the great-granddaughter of Rachel Laws.

1865 : Brown County, Illinois

During the War Between the States, no one had the heart for festivities. Three years ground past, wracked with worry and gloom, but as the war drew to an end, the annual harvest festival made a comeback.

George Riggins took his growing family to the Brown County fairgrounds, and his widowed mother Rachel Briscoe as well. They found Sarah Jane's parents near the hog pens like always, though it had been years since Rachel had last competed.

"Any word about Cousin John?" Sarah Jane asked her father Silas.

"Just a short letter," he said. "Mostly about mosquitoes and the muggy heat. I'd warned him what Louisiana's like in the summer, what my father told about his time defending New Orleans. John says there in Baton Rouge he mostly pulls guard duty over the Confederate prisoners. Boring, he says. He and one particular Reb have a war of insults going on."

Sarah Jane's mother, Martha Jane, took her son-in-law's arm. "We're so glad the draft didn't land on you, George. You know we would have taken in your family, if your luck had soured."

George hugged Sarah Jane, who had three young-uns clinging to her skirts and another in her arms. "We kept busy while waiting!"

"Remember when you had four younger than four, Pa?" Sarah Jane asked Silas, and laughed. "Like Daddy, like daughter!"

"But yours-- Just look at them, all carrot-tops, like their other grampa," Silas said, ruffling every head in reach.

"Have you heard from any of your husband's cousins?" Martha Jane asked Rachel.

"No, and I doubt I will. They know my abolitionist stance." Her husband Mark had come from South Carolina, and most of his kin still lived in the deep South. Rachel grimaced. "Mark and I argued many times over the abomination of slavery, running rampant here in the land of the free. Speaking of cousins, what about William's son John? Any idea when he'll muster out and come home?"

"Soon, they say. By September or October, likely."

"Won't he be glad for high ground!"

Silas nodded. "And the cool evening breezes of autumn."

1872 : Peoria, Illinois

Young George burst in the door. "Uncle John is here!"

George and Sarah Jone both scolded, "Don't slam that door--" but their 10-year-old son had already darted outside again.

Dora Belle looked up from her slate. Though only four, she knew her letters already and had chalked some nonsense words. "Uncle John?"

"The funny one with the curly mustache. Remember?" George said as he took her hand. "He's brought Gramma Rachel to see the new baby. Up you go. Let me dust you off."

When her father brushed her calico smock, the chalk slipped from Dora Belle's fingers, smacked the slate, and broke in half. "Fiddlesticks!" she cried out, setting the grown-ups to grinning.

Two big strangers walked in the door. Dora Belle hid behind her mother's skirts, glad that her uncle and grandmother wanted to coo over the baby and not her.

As Gramma Rachel bent over the cradle, Uncle John guffawed. "Look at that! Another red-head to match the rest." He tousled Dora Belle's fire-bright curls before she could dodge out of reach.

"We're fixing to move," John tossed into the talk about babies. "And take Ma with us."

"Going to join us here in Peoria?" George said.

"Nope. We're heading for Minnesota."

"Minnesota?" Sarah Jane echoed.

"Where's that?" Dora Belle asked Young George.

"Way up north -- a thousand miles, I bet."

"Three, four hundred is more like it," Uncle John said. "I hear tell the wheat fields do well there. I'm afraid Illinois soil is about petered out."

"And you're going, too?" George asked his mother.

Rachel Briscoe tipped her head to affirm. "I can hardly go back to living on my own, not at seventy-two. And you, my fruitful young fellow, have filled every nook in your house with rambunctious youngsters. No room for me."

"But Minnesota--?"

"Why not? Years ago I trekked from the Tennessee mountains across the Kentucky plateau to Illinois prairie lands. Another distant horizon awaits. I'm eager to see the northern land of lakes and forests."

"Going homesteading?" Young George asked, and turned with bright eyes to his parents. "Can we go, too?"

His father shot his mother a questioning look. "Have you had enough of town life yet, dear?"

Sarah Jane's lips thinned. "I do not miss chasing chickens and shoveling manure."

"I'll chase and shovel for you, Ma," young George said.

"Hmm-- How long would that last?" Sarah Jane said. "Well, I'll think about it."

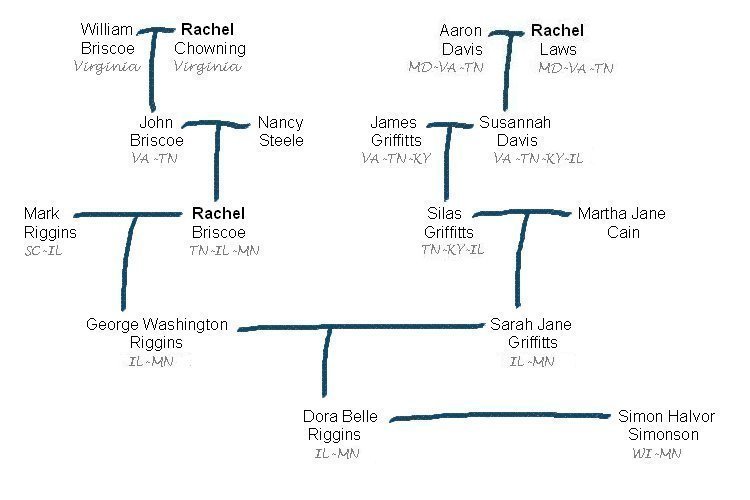

chart of the families in 1872

No date is given for John Riggins moving to Minnesota, but he did take his mother along, according to the 1880 census.

1877 : Illinois to Wisconsin to Minnesota

"I don't see them," Rebecca complained, staring out of the prairie schooner at the unending Minnesota skyline.

"You don't see what?" Dora Belle asked her little sister.

"New horizons. It all looks the same as it did in Wisconsin."

"And as in Illinois," Dora Belle murmured, knowing the five-year-old didn't remember sights from back then. At nine, she knew full well that prairie land meant nothing but flat, flat, flat.

A month ago they had arrived at Uncle John's farm near a town called Meeker. During their short stay, Gramma Rachel had told stories about the mountains of Tennessee where she'd grown up. Dora Belle tried to imagine the landscape rearing up in great humps and ridges.

The covered wagon jolted on a hump in the dirt track. She steadied Rebecca, who leaned precariously out the back.

"Look! A buffalo!" the younger girl cried.

"Nope. Just another cow."

"Is that an Indian?"

"Nope. A scarecrow."

Rebecca flopped down on a pile of blankets. "Fiddlesticks! Minnesota isn't different at all. Just more Wisconsin."

"It'll be good for growing wheat." Dora Belle gazed out the front of the wagon, past her parents' perch. The western horizon shimmered in the afternoon sun, with the mirage of water far ahead on the roadway.

Her parents said a land of lakes lay ahead. One of these days the mirage wouldn't melt away. There'd be water, real water, glistening blue under summer skies, lying like jewels on this vast golden blanket of prairie.

George and Sarah packed up their nine kids and moved to Fulton, Wisconsin, where their tenth child was born. They moved on to Henning, Otter Tail County, in the backwoods of Minnesota, place of the eleventh child's birth. Dates of these moves: unknown.

Otter Tail County lies in the Big Woods area, land of oak, elm, basswood, maple, and black walnut. Further north is the North Woods region of heavy timber.

1880 : Henning, Minnesota

"I've never seen an otter, not all the times we've come looking." Rebecca chucked a stone into Otter Tail Lake.

"Have you seen a map?" Dora Belle asked.

Her sister looked quizzical.

"On a map, the lake looks like an otter tail."

Rebecca blinked. "Oh. Why didn't you tell me?"

"Telling you now. I never knew that's what you thought to find, whenever we came to the lake. I like to just look out at the water, and listen to the birds, and see the land rise up on the far shore."

"Yep -- mountains!"

"Nah, just bluffs. Come on. I hear Pa calling. Must be time to go home."

They ran up out of the wide but shallow dip in the prairie to find their father already seated on the buckboard. Three barrels now were lashed where the hogs had slept on the journey over.

"What did you get in trade, Pa?" Rebecca asked, poking at one barrel.

"A new variety of wheat seed."

"Bah! Boring." She clambered up on the seat beside George.

"And a kitten." He nudged a basket at his feet.

The eight-year-old squealed with glee.

Dora Belle grinned at her father as she squeezed next to her sister who already craded the basket, peering inside.

* * *

When they arrived back at their claim near Henning, Sarah Jane came out to meet them, a sober look on her face. "Young George rode into town and picked up the mail. A letter for you, and one for me. Mine must have fallen between the cracks somewhere along the line. It was all crumpled and smudged." She bit her lip, blinking back tears.

George swung down. "Dora Belle, get Charles to tend the horses."

"I can do it." She led the team toward the barn.

Charles saw her struggle with the harnesses and stepped in to help. Once losed, the mares headed for their mangers. Brother and sister rubbed them down and refilled water buckets. Rebecca took over a vacant stall with her kitten and two younger brothers, all jabbering and giggling and meowing in delight.

When she left the barn, Dora Belle found her parents huddled close together on the bench outside the cabin door, both red-eyed and drawn. Sarah Jane beckoned over Dora Belle and Charles to give them the news. Gramma Rachel had died, Uncle John wrote. Eighty years old. Fine one day. Gone the next.

And Grampa Silas, way off in Illinois, had died nearly a year ago, the letter lost in the mail for all that time.

Stricken silence in the courtyard. Giggles in the barn.

I'm not a silly child anymore, the twelve-year-old realized as she shared in the weight of her parents' sorrow. This is what it feels like to be grown up.

Silas' death is listed as "before 1880."

In the 1880 US census, Rachel Briscoe appears in the household of her son, John Riggins, living in Meeker, Minnesota; the count must have been made before her death that year.

Among Rachel's descendants, two granddaughters will share her name.

1898 Otter Tail County Railroad Map

Henning is in the lower right, to the right of Battle Lake

1886-1887 : Henning, Minnesota

After years of hard work, the Riggins farm at last began to thrive. George and Sarah Jane figured the family had earned a few days off. They piled into the buckboard and went to the county fair.

"Too bad Mary and Charles have to miss out," Rebecca gabbed as they trooped onto the fairgrounds. "That's what they get for abandoning the family."

"It's not 'abandoning' to find sweethearts and get married," Dora Belle said.

"I'm never going to marry. Boring."

"Hah!" Dora Belle replied. "If love ever smacks you upside the head, you'll be getting married within the week."

"Well, if I do, at least I'll make sure no one else gets married on the same day. I'd want all the fun and glory for myself."

Dora Belle rolled her eyes. "Charles and Mary are the ones who dreamed up sharing the big day. 'Sharing' is the word."

Their four older brothers each took one arm and ushered the sisters apart. "No bickering today, girls. Come see the sights!"

They passed a booth displaying colorful blouses. Two tall blond women spoke to onlookers, pointing out the rich emboidery.

"What are they saying?" Rebecca's voice floated back to Dora Belle. "I can't understand a word!"

"Swedes," said Young George from Dora Belle's left.

"I don't think so. Germans, I'll bet," said Frank on her right.

"Norwegians," Dora Belle said. "That's what my friend Hilda sounds like when she talks with her folks. And look, there she is! You can let go now. Hilda and I have better things to do than pester Rebecca."

Hilda gave Dora Belle a peck on the cheek, then led her on a winding path through the crowds. "I'm so glad you finally came to the fair! I've told my cousins and second cousins all about you." She made one introduction after another to lanky youths and tall willowy maidens.

"What are they saying?" Dora Belle asked.

"They love your red hair, and think you'll make a lovely woman when you grow up. I keep telling them you're already eighteen! Come on, let's join the dancing, my little red-capped elf of a friend!"

Hilda taught Dora Belle a few steps first, off to the side, and interpreted the calls of the dance-master. Dora Belle felt like a child in the midst of the tall rambunctious Norwegians. She couldn't keep to the proper steps since she had to take two for every stride of her partner.

Laughing, she fell out to catch her breath. Hilda got swallowed up in the swirl of dancers. Dora Belle hopped up several times, but couldn't spot her.

"Are you lost, little girl?" someone asked with a heavy Norwegian accent. A tall dark-haired fellow had also dropped out of the dance.

"I don't know how Hilda will find me again." Dora Belle looked around, spied a wooden crate beside a table laden with food. "That will even the odds!" She hopped up, but the crate wobbled on a rut.

The fellow grabbed her arm to steady her.

"Takk," she told him, using one of the few words she'd picked up from her friend. She gazed over the dancers' heads and waved. "Ah, good. She sees me."

The tall fellow helped her down again. "Would you like a plate of kringla?" he asked, pointing at a platter of sugared and layered flatbreads.

"Ja, takk. I'm not a little girl, you know."

"Oh ja, I see that now."

Hilda laughed to find Dora Belle craning her neck up to chat with the friendly fellow who towered over her. "If you don't want a crick in your neck," Hilda said, "you may need to go back to perching on that crate. Or Saamund could sit down, perhaps."

"Poor manners to sit while a lady stands," he replied.

Dora Belle learned more dance steps, thanks to Saamund. (He didn't seem to mind when she pronounced it "Simon.") He shortened his stride to match hers, and had to lean a little to make the proper holds.

Meeting in the middle, Dora Belle thought, and grinned. "This dance with the jig in the rhythm--"

"It's called a springar step," he said.

"--I think my feet have finally caught the pattern. The music is like magic! Fast and bright and haunting all at once. I've never heard a fiddle played that way."

"Hardanger-style," Simon said. "I play, a little. My mother taught me a tune or two on her fiddle from the old country. Simple tunes."

"Really? May I watch sometime, close up? Sometime. If ever, well, if--" Dora Belle blushed. She'd only just met him, and here she was babbling, hinting she'd like to see him again.

He didn't answer, not with words. But his eyes held a sparkle unlike any she'd seen before.

When Simon introduced Dora Belle to his family, they nodded politely and greeted her in broken English, then rattled off long strings in Norse to him, which he waved aside. Much later she learned they were protesting his interest in a young woman from outside the tightly-knit Norwegian community.

But something had smacked him upside the head, and their words fell on deaf ears. A month later, tall lanky Simon came courting the petite red-head. He brought his fiddle along and granted Dora Belle her wish.

After the turn of the year they married, taking a homestead right next to that of his parents.

chart of the families in 1886

Oscar's son Norval often recounted his memory of his grandmother Dora Belle walking underneath Simon's outstretched arm -- without even ducking.

1894 : Henning, Minnesota

Dora Belle whisked laundry off the line. The sheets and diapers smelled of smoke. So did her hair. So did every breath of air.

Midday sun beat through the sluggish haze, dim but relentless. The first week of September, and still sweltering hot. Awkwardly she hoisted the basket and headed back to the shade of the cabin.

Door and windows stood open in hopes of a breeze. Her three children sprawled on the bed, playing with the little wooden figures Simon had carved for them last winter. Dora Belle poured them all drinks of well water, then sat and fanned herself.

Hoofsteps clattered up the lane and into the farmyard. Dora Belle poured another glass of water, then doused a corner of her apron and wiped her brow. Summer heat, a boon to the wheat, but not to a woman heavy with child.

Simon came in after stabling his horse. He downed the glass of water, poured himself another, and sank into the other chair. He gave his head a weary shake. "Four hundred square miles, gone up like a torch. The firestorm destroyed Hinckley and Brook Park and four other towns."

"But that's near Duluth," Dora Belle said. "A hundred and fifty miles away! Why so smoky here?"

"Other fires, burning along the railways and around the logging camps. Nothing we can do about it but pray the wind shifts." Simon blew out a long breath. "More bad news. Northern Pacific Railway just filed for bankruptcy. Railroad workers going on strike. U.S. cavalry called out to guard the rails. More and more hoboes swarming out of the east, thieving along the way." He plunked down his glass with a thump. "And the price of wheat just dropped again."

"How long can this go on?" Dora Belle whispered.

Six-year-old Reimund was watching with a worried look, but the little girls played on.

Simon placed his hand over hers. "Good thing we doubled our acreage last year. Should be enough to keep us afloat. Don't worry. Every farm has its bad years."

* * *

Two weeks later the wind shifted, the air cleared, and Dora Belle went into labor. Simon took the children to stay with Hilda. His mother, Tone, served as midwife.

Between Tone's broken English and Dora Belle's scattered grasp of Norwegian, they managed well enough. Words don't matter much anyway when it comes to the speechless agony of the birthing itself.

Afterwards, in the midst of a swirl of relief, Dora Belle understood just fine when Tone declared, "Congratulerer! En vakker dotter!"

"A daughter," Dora Belle panted, and lay back. "Flora and Mary will be delighted, but poor Raymond. He wanted a brother."

Tone asked a question. Dora Belle heard a couple words she recognized. Name. Mother.

She knew it was Norwegian custom to name children after their grandparents or other close relatives. She smiled. "My farmor. We'll name her after my father's mother. We'll name her Rachel."

Raymond/Reimund later gained five brothers. And two more sisters.

The three-year-long Panic of 1893 was

"a severe economic meltdown that was surpassed in its tragic impact

only by the Great Depression that followed four decades later."

1902-1905 : Henning, Minnesota

"Regular as clockwork," George Washington Riggins told his son-in-law Simon as they cleaned tack together at the Simonson farm. "Every two years, you give us another grandchild, spaced so nicely apart. I do believe Sarah Jane is jealous. She went through childbirth almost every year for a while. Why, when Dora Belle was born, that made it six children under seven years old!"

"Busy." Unlike the fiery, talkative Irish, Norwegians kept chat to a minimum.

"You should have seen the washline. Diapers always flapping like flags at a parade."

Flora and Mary, Simon's two oldest daughters, burst in through the barn door, dancing with excitement. "Pa! Grampa! A boy!"

Simon leaped up with a grin, took each girl by the hand, and strode to the house.

Grampa George took longer to rise. At sixty-six, his muscles stiffened when sitting too long, and they'd been waiting quite a while. By the time he came inside, Gramma Sarah Jane was tossing linens in a wash bucket. She gave him a weary smile.

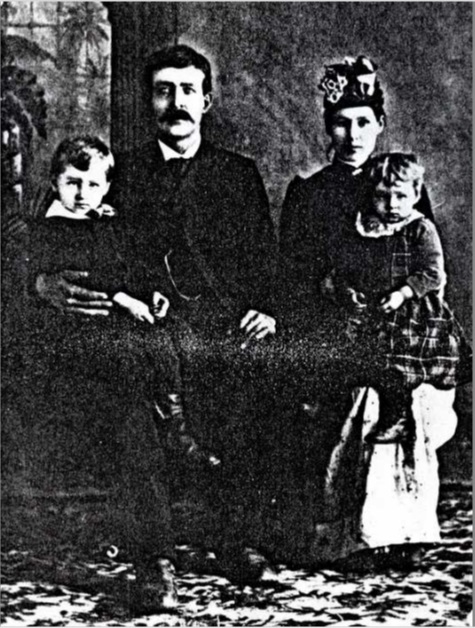

The girls leaned on the bed, watching their mother cradle a tiny bundle, and cooing at their new brother. Simon stood beaming at the head of the bed, twitching his dark mustache in pleasure like a cat might twitch its tail.

"What's his name going to be?" Mary asked.

"Not yet, not yet," Dora Belle said. "Wait till everyone's here."

"Go tell Reimund to saddle up and ride to Hilda's," Simon said. "Time to take the young-uns off her hands."

Flora pushed Mary toward the door. She pouted, then ran off.

Grampa Halvor and Gramma Tone walked over from their homestead just up the road. Friends and neighbors gathered, bringing food and the rest of Simon's brood. Rachel, eight, and Oscar, six, led in the four- and two-year-olds to crowd around the bed and goggle at the baby.

Silence fell as Simon stood and stuck thumbs behind his suspenders. He cleared his throat and spoke in Norwegian to his parents. "Our new little son shall be named Silas."

Dora Belle grinned up at her mother, Sarah Jane. "We're naming our baby after your pa!"

"Just like I'm named after your ma!" Rachel said, tugging on Grampa George's arm.

He sat and pulled her close. "It's a very special name, you know. I hope you wear it well." He tweaked her nose.

"Grampa! How can I wear a name?"

chart of the families in 1902

Rachel and Oscar stood side by side on the porch, waving goodbye. Their father Simon drove a buckboard, taking his parents-in-law back to the train station.

"I wish Grampa George and Gramma Sarah could live next door, like Farmor and Farfar do," Oscar said.

Rachel squeezed his hand. "So do I. A thousand miles is a long ways away!"

When the wagon had vanished from sight, the two ran to their Norwegian grandparents' cabin for more stories of Norway: mountains rearing against the sky, trolls haunting bridges across steep gorges, maidens stolen away to a magical underground realm. Though neither child could say much in Norwegian, they understood it well enough.

And they both loved to listen to Farmor Tone play the fiddle.

"Will you teach me?" Oscar asked one day, and mimicked sawing away.

"Show me your hands." Tone inspected his fingers. "Ja, I think you're big enough now. Here. Tuck the belly beneath your chin, and hold the neck like so."

"What about the fiddlestick?" Rachel asked, pointing.

"Ah, the bow. Take it like so. Now let it glide across the string like petting a kitten."

Rachel clamped hands over her ears. "Kitten? Fiddlesticks. Sounds like a bad-tempered tomcat!"

Simon, Dora Belle, Raymond (?) and Flora (?) in 1892?

Three years later, when the next Simonson boy was born, Dora Belle snuggled her newborn, smiling and weeping both at once.

"What will we call him?" Rachel begged to know.

"He's going to wear your Grampa's name, in his memory."

"George Washington Simonson!" Rachel bent over the baby. "I'm so sorry, Little George."

"Sorry for what?"

"That he won't get to know his Grampa like I did."

George Washington Riggins died in 1904 in Spokane, Washington, where he was living with another son, according to the 1900 US census. Could he and Sarah Jane have traveled by train to Minnesota for a visit?

The Northern Pacific Railroad would have served that route at that time. In 1912, railroad fare from Seattle to Chicago cost $65 ($1700 in today's dollars, after inflation).

1908 : Minnesota to South Dakota

Rachel Simonson was fourteen the year her family got news from Washington State, a thousand miles away, that her Gramma Sarah Jane had died.

That wasn't the only farewell. Her parents sold their farm.

"Time to go west," Simon told the family. "I hear tell there's better land to be had in Nebraska."

"Leave?" Rachel asked, her stomach doing a flip. All her fourteen years, she'd lived here in Henning. Grandparents, friends, her favorite haunts -- how could she leave them all?

"Where's Nebraska?" Oscar asked.

"West." Simon shrugged. "Won't be hard to find."

As Dora Belle packed, she looked as unhappy at the prospect as Rachel. "I wonder if my mother felt this way when she left Illinois," she murmured. "Or my Grampa Silas, leaving Tennessee."

Simon harrumphed. "My parents left their homeland behind. Fjells and fjords and all. Left it far beyond the sea, beyond the horizon, and never looked back."

"Never?"

"Vel, not often. My father does sometimes say he longs for the sight of a hill among all these wide prairies."

* * *

The family loaded up two covered wagons, leading three horses and a cow behind. The family dog, Rover, dashed about, wagging, nosing everyone, eager for adventure.

The Norwegian grandparents, now aged 72 and 74, came to say farvel. Halvor handed Simon a pouch that clinked. "Five dollars to help on your way." They shook hands, ever so calm, but both men seemed to get something in the eye at the same moment.

Tone handed to Oscar the fiddle case. "Too much pain in my old fingers," she said. "Time to pass it on. Practice every day. Make the fiddle sing for me."

The twelve-year-old hugged first the case, then his gramma. "Takk, tusen takk!" he told her in clumsy Norwegian. "I will make it sing."

Rachel took one last glance at the weathered cabin and stubbled fields of home, then climbed up beside her big brother Raymond who drove the second oxteam. Rover dashed ahead as they took to the road.

* * *

Sixty-some miles into the west, the track started an overall downward slant. "This here's the Red River Valley," Simon called back from the lead wagon.

"That's the name of a song!" Rachel said, and hummed the tune for Oscar to try on the fiddle.

"No more of that, not on my wagon," Raymond told the two of them after an hour's sawing at the melody. So they traded places with Flora and Mary.

The track led down to a sluggish river, shallow at the ford. The two wagons easily rolled across. The waters of the Red River only came up to the axles. Rover leaped into the current and paddled across faster than the oxen could trudge.

The land rose again. For three hundred miles, Rover pestered every traveler they passed, spooked horses, chased jackrabbits, tried to join in on a passing cattle drive until the working dogs ganged up and drove him off. He wouldn't come to anyone's call, though he sometimes answered Rachel's whistle.

"I declare," Dora Belle said more than once. "That dog is about as useless as a two-headed calf."

Their trek brought them to the banks of the Missouri River, far too wide to ford. Simon spent his last dollar paying for passage on a ferry for both wagons and their livestock.

Rover ran up and down the shore, barking protest. He obviously did not like the looks of the floating contraption, and would not answer calls nor whistling nor the dubious lure of stale bread. "I bet he'd come if we had fresh meat," Rachel said.

"Or a cat in a basket," Oscar added.

Rover ran back up the bank as if saying, "Enough journey -- let's go home now."

"Fiddlesticks," Simon said, picking up a term that Dora Belle often used. "There is nothing to do but to leave him."

Rachel watched the dark spot that was Rover growing smaller on the bluff as the ferry-man poled off. "My grampa paddled a canoe up and down the Missouri," the grizzled old fellow said. "A hundred years ago, it was. He trapped in the wild woods. A fur trader, yep, that was Grampa. Care to try the current in a birchbark canoe, Missy?"

"No thank you!" Rachel clung to one of the wagons, strapped securely in place, as the ferry tilted underfoot. Gulping, she tore her gaze from the swirling, muddy current and fixed it upon the western horizon.

The ferry-man chuckled, then broke into song. "Away, we're bound away 'cross the wide Missouri."

Oscar grinned to hear a new tune.

He pulled out his fiddle and set to tuning.

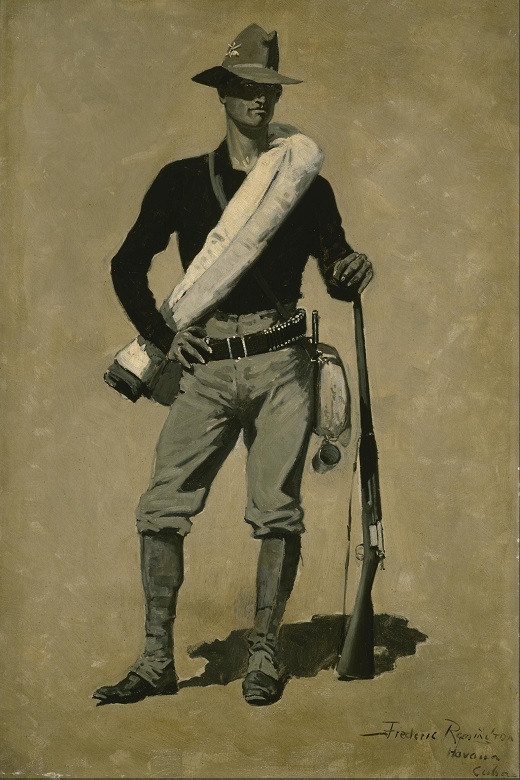

Charles Deas' The Trapper and his Family (1845)

depicts a voyageur and his Native American wife and children

lyrics to

Red River Valley

and the ferryman's song:

Shenandoah

Source of account about Rover

1910 : South Dakota to Nebraska

Simon and Raymond looked for jobs in the town the other side of the river. For two years the family lived near Mobridge while they saved up funds to continue their journey, living in their wagons until they found a ramshackle cabin to rent for a pittance. Then once again they set off, heading west. No matter how far they traveled, the horizon lay flat and unbroken before them.

"How much further?" Oscar kept asking.

"We'll get there when we get there," Simon said, nodding toward the sunset.

Then one day a girl came along riding a wiry little pinto. She traded howdies with Flora and Mary, and gave a cheeky grin to Raymond. "Where ya heading?" she asked Simon and Dora Belle.

"Nebraska."

"Really?"

"Yup."

"Won't get there by going west. That's the way to Montana."

Simon hummed a moment. "Which way to Nebraska?"

The girl pointed due south. "Take the left fork up ahead. When you come to the next dry wash, follow it south and you'll come to a track that'll take you to Valentine."

"In Nebraska," Rachel said.

"Yup."

"Much obliged," Simon said.

"Thank you!" Dora Belle added, then muttered, "Just keep going west, you said. I knew we should have asked for directions at the last homestead!"

Another couple hundred miles brought the family to the prairies of Nebraska. They rolled past scattered fields of wheat waving golden in the midsummer sun. Simon nodded at the good prospects.

"About time," Dora Belle said with a sigh, and rubbed her aching back. "I wouldn't be good for much longer."

The wagons forded one last creek*, then the bare trace of a trail turned into a regular track. Several cabins came into view. Dora Belle pointed out a woman hoeing in a kitchen garden close to the roadside. "I'll have a word," she said.

Simon and Rachel helped her down from the buckseat. Dora Belle smoothed down her dress, which was growing a little too tight for her condition, and went to ask about the settlement.

She returned with a satisfied air. "Yes, this is Valentine. I like the sound of that. And land is to be had for a song."

Oscar nudged Rachel. "I'll get some for myself then!" He mimed bowing a fiddle.

"Sure," she scoffed. "A fourteen-year-old homesteader."

Raymond mussed his brother's hair. "I'll let you come work on my claim till you're old enough for your own."

"Let me?"

"Camping is allowed the other side of the general store," Dora Belle told Simon as he hoisted her back up on the wagon. "But don't take too long in scouting for our own claim. I'll need at least a tent before this baby decides to come."

As Simon prodded the oxen back into motion, a couple young men passed the wagons, hiking up the road into town with shovels over their shoulders. One of them gave Rachel a wink.

She smiled back, feeling her face grow warm. She too liked the sound of Valentine.

lyrics to a song about * Minnechaduza Creek

the next 100 years: Nebraska to Wyoming to the Washington coast

At their new homestead in Valentine, Nebraska, Dora Belle bore one last baby. Youngest son Jesse would later write his life story, including some of his parents' tales of life in Minnesota, the fiasco of their quest to find Nebraska, and the fate of poor old Rover.

Jesse's big sister Rachel spent the rest of her days in Nebraska. She married and had ten children.

Jesse's big brother Oscar trained to run the steam engines that powered farm tractors and combines, but his promising career fizzled when the diesel engine made steam power obsolete. He and his young wife Nida then took a land claim in Wyoming. Hard work, ingenuity, and integrity enabled them to survive the Great Depression.

Oscar's son Norval -- who spent a year trying to learn to play his father's violin -- carried one branch of the pioneering family even further west to Washington state.

Nine generations blazed a path from sea to shining sea, from sunrise over the Atlantic to the Pacific's shimmering sunset horizon.

Oscar's son Phil mentions the family violin, but questions remain. Did Oscar inherit it from Norwegian grandparents? Or gain it in trade during the Depression?

Oscar's son Norval practiced on that violin for a full year, but everyone was glad when he gave up in defeat.

Norval's trademark outburst at aggravations

such as that wasted effort:

"Fiddlesticks!"

Appendix A : family history extracts

~ "50 Years in the Sandhills and Forest," pages 1-3, by Jesse Simonson (last son of Simon and Dora Belle)

Father had come to Henning, Minnesota, with his parents when they homesteaded there. This is where he met my mother. When they were married, they took a homestead beside his folks' place...